Thermoplastics are one of two major groups of plastics, and include nylon, polyethylene, polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride, and dozens of other kinds.

They are used to make thousands of consumer and industrial products ranging from toothbrush bristles to soda pop bottles to car bumpers.

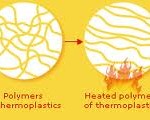

In deriving thermoplastics, the process need heat (or chemicals) to harden from its liquid state into a final shape, and can be melted and remolded time and again.

The other group of plastics, are the thermosetting plastics, they harden once and can’t be remelted again.

Yiqi Yang, PhD, an authority on biomaterials and biofibers in the Institute of Agriculture & Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, pointed out that both kinds of plastics are made mainly from ingredients obtained from oil or natural gas.

Due to volatility of petroleum supplies, prices, and sustainability, dozens of scientific teams are working to find alternative ingredients.

One aspect is to use agricultural waste and other renewable resources to make bio-plastics that can be biodegradable once discarded into the environment.

Chicken feathers are an excellent prospect, Yang explained, because they are inexpensive and abundant. Annually there are more than 3 billion pounds of waste chicken feathers in the United States alone.

Chicken feathers are made mainly of keratin, a tough protein also found in hair, hoofs, horns, and wool that can lend strength and durability to plastics, according to Yang.

The mechanical properties of feather films outperform other bio-based products, such as modified starch or plant proteins.

The thermoplastic derived from feathers of chicken had excellent properties, it has been found to be substantially stronger and more resistant to tearing than plastics made from soy protein or starch, and had good resistance to water.