Italy’s economy experienced little growth starting in the late 1990’s, when the country’s manufacturing was overtaken by competitors in Asia.

Then came the global financial crisis in 2007, which shrank Italy’s economy by more than 6 percent. Hindering economic growth is Italy’s gasping government debt, which at 119 percent of gross domestic product is second only to Greece’s among euro zone members.

Although it has run a budget surplus, minus debt costs, for several years and recently passed a 48 billion euro deficit reduction plan, the Italian government now spends 16 percent of that budget on interest payments.

Six years ago, the Swedish retail giant Ikea planned a 60 million euro megastar just a few kilometers from where the Tower of Pisa leans into the earth. Backers said the huge construction project, new roads and wave of shoppers would bring hundreds of sorely needed jobs to this rural corner of Tuscany.

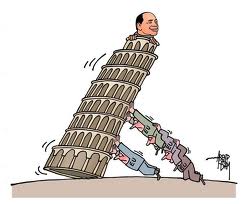

But things got tangled, as they often do in Italy, where bureaucracy and politics can easily overwhelm economics. As Italy teeters on the edge of the European debt crisis, it cannot afford more setbacks like that one.

Otherwise, despite having the world’s seventh largest economy, Italy may have little hope of outgrowing the staggering debt load that could threaten its financial future, and that of the euro monetary union.

The amount of Italy’s debt held by foreigners, nearly 800 billion euros, is more than that of Greece, Ireland and Portugal combined. Should Italy stumble, the aftershocks would be more disruptive than anything the euro zone has felt so far in the crisis.

As higher, interest rates make it even harder for Italy to reduce its debt, the main recourse would seem to be faster growth.

Growth has resumed, but the International Monetary Fund predicts ‘another decade of stagnation,’ with Italy’s gross domestic product expanding by only about 1.4 percent annually in the next few years.

The barriers to growth make for a daunting list. For starters, national leaders like Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and even mayors of the smallest towns tend to be caught up in politics that distract them from the economy’s plight. And corporate taxes are around 31 percent, not counting an array of local taxes on businesses.

Italy must not only encourage big corporate investments like the Ikea project, experts say, but also remove impediments that stifle growth in the thousands of small and medium size companies in its economy.

Italy is also plagued by a black market that is estimated to make up to 20 percent of the economy. Few believe the government can easily eliminate the black market economy. But Italy’s leader could start untangling the bureaucracy that ensnared Ikea and put strain on thousands of smaller companies.