Scientific evidence confronts dieters, reducing calories alters your metabolism and brain, so your body hoards fat and your mind magnifies food cravings into an obsession.

New research shows dieting raises levels of hormones that stimulate appetite and lowers levels of hormones that suppress it.

Meanwhile, brain scans reveal that weight loss makes it harder for us to exercise self-control and resist tempting food.

It’s also thought the brain changes in the way it reacts to food. This wilts our willpower, according to Michael Rosenbaum, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center who studies the body’s response to weight loss.

‘After you’ve lost weight, there’s an increase in the emotional response to food,’ he says, adding that there is also ‘a decrease in the activity of brain systems that might be more involved in restraint’.

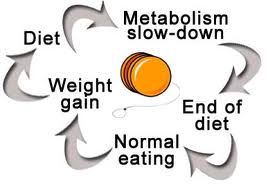

Our calorie-hoarding frames have strong mechanisms to stop weight loss, but weak systems for preventing weight gain. If you manage to lose ten per cent of your weight, your body thinks there’s an emergency. So it burns less fuel by slowing your metabolism.

The body learns to function on fewer calories, resetting your metabolism. The problem is if you then stop dieting and start eating more again, those extra calories are stored as fat.

Worse still, the more people diet, the stronger these effects can become, leaving some almost doomed to being overweight as a result of their attempts to become slim.

And as research lays bare the dangers of yo-yoing weight, some experts argue it would be better not to diet at all.

Scientists at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York discovered that when starved of food, brain cells actually consume each other.

This causes the release of fats, which in turn results in higher levels of a powerful brain chemical that stimulates appetite, the journal Cell Metabolism reports.

All bad news for dieters, as going without food could make them even hungrier.

All of this helps to explain why an analysis of 31 long-term clinical studies found that diets don’t work in the long run. Within five years about two-thirds of dieters put back the weight and more.

The researchers from the University of California found that dieting works in the short term, with slimmers losing up to 10 per cent of their weight on any number of diets in the first six months of any regimen.

But after this, the weight returns, and often more is added, says their report in the journal American Psychologist.

The analysis concluded that most volunteers would have been better off not dieting. Their weight would be pretty much the same and their bodies would not have wear and tear from yo-yoing.

People who start habitually dieting young tend to be significantly heavier after five years than teens who never dieted.

This mix of biology and psychology translates into a sobering reality, once we become overweight, most of us will probably remain that way.

Certainly, we should all be worried about what dieting does to our health. Restricting calories may increase the risk of heart disease, diabetes and cancer, according to a study from 2010 in the journal Psychosomatic Medicine.