The United States Geological Survey calls the rare earth minerals “essential for hundreds of applications” and candidates in the near future for an “expanding array” of hi-tech products.

Supply shortages that go on for a long time, the agency warns in a fact sheet, ‘would force significant changes in many technological aspects of American society.’

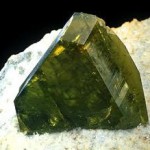

The minerals known as manganese nodules, the rocks have some concentrations of nickel, copper and cobalt as well as manganese and other elements, but lie miles down in a murky abyss of the ocean floor.

For decades entrepreneurs have tried to get wealthy by gathering up the ugly potato size rocks that carpet the global seabed.

Building giant machines to vacuum them up has never proved to be economical. The nodules turn out to contain so called rare earth minerals, elements that have wide commercial and military applications but have hit a production roadblock.

China which control 95 percent of the world’s supply, had blocked shipments, sounding political alarms around the globe and a rush for alternatives.

Despite signals that China was lifting the ban, observers say it is still blocking shipments to Japan, and the hunt for other sources continues.

In October, James R. Hein, a geologist with the United States Geological Survey and five colleagues from Germany presented a paper on harvesting the nodules for their ‘rare and valuable metals.’

The elements known as rare earths number 17 in all and range from cerium and dysprosium to thulium and yttrium. Their unique properties have resulted in their growing use in many technologies of modern life.

Applications include magnets, lasers, fiber optics, computer disk drives, fluorescent lamps, rechargeable batteries, catalytic converters, computer memory chips, X-ray tubes, high temperature superconductors and the liquid crystal displays of televisions and computer monitors.

Most rare earths are not particularly rare. But their geochemical properties mean they seldom concentrate into economically exploitable ore pockets.

During the last two decades, most production has shifted to China because of lower costs there and the country’s record of lax regulation of environmental hazards. (The processing of rare earths can create toxic byproducts)

Scientists have known about rare earths in seabed rocks for decades, seeing them as a curiosity.

Charles L. Morgan, chairman of the Underwater Mining Institute said that he was considering whether to start analyzing a collection he oversees of 5,000 nodule samples from around the globe so as to ascertain their rare earth content. But he cautioned that the field of seabed mining has a history of ups and downs.