As a result of human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels for energy and land-use changes such deforestation, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is now higher that it has been at any time over the last 800,000 years .

Man-made carbon emissions have acidified the world’s oceans far beyond their natural levels, new research suggests.

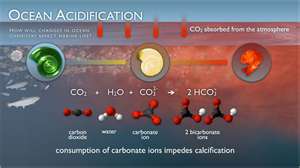

“The oceans absorb around a third of carbon dioxide emissions, which helps limit global warming, but uptake of carbon dioxide by the oceans also increases their acidity, with potentially harmful effects on calcifying organisms such as corals and the ecosystems that they support,” explained Dr. Toby Tyrrell of the University of Southampton’s School of Ocean and Earth Science (SOES) based at the National Oceanography Center, Southampton.

Changes in ocean pH over subsequent centuries will depend on how much the rate of carbon dioxide emissions can be reduced in the longer term.

In some regions, acidity levels rose faster in the last 200 years than it did in the previous 21,000 centuries, a study from the University of Hawaii has shown.

Measuring changes in ocean acidity is difficult because it varies naturally between seasons, years and regions.

Ocean acidity makes it harder for organisms such as molluscs and coral to construct the protective layers they need to survive.

Scientists looked at changes in the saturation level of aragonite, a form of calcium carbonate used to measure ocean acidification.

As seawater acidity rises, the saturation level of aragonite falls.

The peak year of emissions and post-peak reduction rates influence how much ocean acidity increases by 2100.

The new research used simulations of ocean and climate conditions going back 21,000 years to the Last Glacial Maximum and forward in time to the end of the 21st century.

“Our computer simulations allow us to predict what impact the timing and rapidity of emission reductions will have on future acidification, helping to inform policy makers” said Dr.Tyrrell.

Aragonite saturation in several key coral reef regions is already five times below its lowest pre-industrial range, according to the model.

This translates to a decrease in overall calcification rates of corals and other shell-forming organisms of 15 percent, scientists at the university believe.