In Dusy Basin, in California’s Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, Vance Vredenburg, a professor of biology at San Francisco State University, is conducting an experiment he hopes will help preserve what remains of the once abundant frogs.

Dr. Vrendenburg, 41, has been doing frog research in the Sierra range since the 1990s when he and colleagues counted 512 amphibian populations scattered among the thousands of mountain lakes.

By 2009, 214 of these populations had gone extinct. A further 22 showed evidence of the disease.

A deadly fungal disease threatens frogs to global extinction and has also caused the decline of 40 percent of the world’s frogs, toads and salamander in the Sierra Nevada of California.

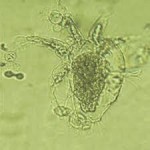

Chytridiomycosis, or chytrid, which has already driven at least 200 of the world’s 6700 amphibian species to extinction for the last decade, has laid waste to the indigenous Sierra Nevada yellow legged frog, Rana sierrae.

Dr. Vredenburg and his colleagues are inoculating chytrid infected frogs with a bacteria, Janthinobacterium lividum, or J. liv. It does not prevent infection but seems to mitigate it and may help frogs to survive.

Dr. Vredenburg and colleagues discovered the symbiotic bacteria on several amphibian species during laboratory experiments last year. They showed that J. liv. produces a metabolite, violacein, that is toxic to the chytrid fungus.

Dr. Vredenburg’s research showed that chytrid spreads in a linear wave across the landscape, an infection pattern like that of human epidemics. Infection levels start out light, then increase to very high. Then there is a mass die off.

Dr. Vredenburg and his students placed experimental frogs in plastic containers for an hour long bath in cultured J. liv., long enough to colonize on frogs’ skins. They released the frogs into the ponds and streams where they had been captured.

Several weeks later, Dr.Vredenburg had results from the laboratory: all the frogs caught earlier were infected with chytrid. The inoculated ones had the lowest levels of infection.

Dr. Vredenburg is hopeful about his experiment, but like many of his colleagues, he is not optimistic about the future of amphibians.