In a report published in Science of last year, it was based on an experiment where subjects had distributed money to both “in and an out group” of people.

Carsten K.W. De Dreu of the University of Amsterdam and colleagues found out that doses of oxytocin made subjects more likely to favor the ‘in group’ than the ‘out group’.

With a new set of experiments published in the January issue of the Proccedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Dr. De Dreu has extended his study to ethnic attitudes, using Muslims and Germans as the ‘out groups’ and Dutch college students as the ‘in group’.

These references were chosen because of a 2005 poll that showed 51 percent of Dutch citizens held unfavorable opinions about Muslims, and other surveys regarded the Germans as “aggressive, arrogant and cold.”

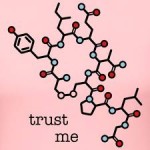

Oxytocin is described as a brain chemical, released from the hypothalamus region of the brain. It is something that gives rat mothers to nurse their young, keep male praire voles and what is remarkable it makes people trust one another even more.

New studies, however, suggest that oxytocin has limits. The love and trust it promotes are not towards the world but just toward a person’s in group.

Psychologists including De Dreu have concluded that oxytocin is the agent of ethnocentrism, a very basic part of humans and it’s not something that can be changed by education.

The Dutch researchers found some evidence that the brain chemical enhances negative feelings, though this is not conclusive. “Oxytocin creates intergroup bias primarily because it motivates in group favoritism and because it motivates out group derogation,” they wrote.

Despite the limitation on oxytocin’s social reach, its effect seems to be achieved more through inducing feelings of loyalty to the in group than by tormenting hatred of the out group.

Dr. De Dreu plans to investigate whether oxytocin mediates other human social behaviors that evolutionary psychologists think evolved in early human groups. Besides loyalty to one’s own group, there would have been survival advantages in rewarding cooperation and punishing deviants.

Oxytocin, if it underlies these behaviors too, would perhaps have helped ancient populations set norms of human behavior.

Bruno B. Averbeck, an expert on the brain’s emotional processes at the National Institute of Mental Health in Maryland, said that the effects of oxytocin described in Dr. De Dreu’s report were interesting but not necessarily dominant.

The brain weighs emotional attitudes like those prompted by oxytocin against information available to the conscious mind. If there is no cognitive information in a decision to be made whether to trust a stranger whom nothing is known.

The brain will go with the emotional advice from its oxytocin system, otherwise rational data will be weighed against the influence from oxytocin and may will override it, according to Averbeck.

Dr. Averbeck was amazed that oxytocin can affect such a high level of human social behavior.