Benefiting from years of low interest rate that followed the creation of the euro zone in 1999, Irish economy enjoyed one of the biggest growth spurts in Europe.

But inflation adjusted economic activity per person has since fallen about 18 percent.

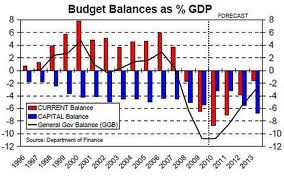

After a stunning plunge fueled by a disastrous banking collapse, the economy has fallen back to where it was in 2005.

For many Irish, it is as if the boom never happened. And some of those floated up during the good times now see themselves slipping even further behind.

Brian and Rosie Condra are among hundreds of thousands of Irish whoever the last few years, finally started to catch up with and even surpass many of their European neighbors.

As part of Ireland’s effort to pay down its immense debts and bailout the banks, the Condra’s salaries from their state jobs as hospital workers have been cut 20 percent in two years.

Moreover, the European Central Bank, for the first time in three years, is raising interest rates which will increase borrowing costs on existing home loans.

That frightens the Condras even more. They are terrified that they will not be able to pay their mortgages and could move into social housing.

Even people with good incomes are convinced that Ireland is facing years, perhaps a full generation, of economic struggle. And with unemployment at 14.7 percent, thousands of young Irish people continue to leave the country to find work.

Exports from multinational companies or manufacturers are increasing as wages become more competitive and help to lower production costs.

Signs of a real estate recovery have even emerged, with buyers flocking to recent auctions to snap up distress properties.

Two years ago, Mr. Condra’s take home pay as a hospital porter in Dublin was 1200 euros (US$ 1200) a month, until their fortunes suddenly changed when Ireland banks went bust and the Irish government decided taxpayers would pay the full bill which adds up to more than 10,000 euros per person. Mr. Condra now earns 240 euros (US$ 344) less a month.

The biggest fear is that growth and jobs are not going to return as quickly as promised. Angry voters swept out the government in March, making Ireland the first euro club member to punish its leaders for their handling of the economy.

But, the new prime minister, Enda Kenny, has little choice but to follow the austerity blueprint, which the International Monetary Fund now acknowledges is delaying recovery. The fund cut its 2011 growth forecast to 0.5 percent, down from 0.9 percent.