One factor in Vladimir V. Putin’s selection as president was a survey that showed that Russians’ most admired figures were fictional tough guys, said Igor V. Zadorin, who headed the Kremlin’s in house sociology department.

Mr. Putin’s approval ratings climbed as he crushed resistance in Chechnya and brought rebellious oligarchs to heel.

As a result, polling data has become an essential part of governing. It will play a significant role in deciding who will become president next spring, Mr. Putin or the incumbent, Dmitri A. Medvedev, and how the campaign will be waged.

The people who run autocratic Russia are obsessed with approval ratings. Political competition has been all but extinguished since Mr. Putin came to power, but Kremlin insiders see popularity as a key to the survival of a government that, 20 years after the Soviet collapse, has few stable state institutions other than its leaders’ personalities.

Mr. Putin remains dominant, even as he has gone from the presidency to the prime minister’s office. This system which has developed over 10 years is based on the support of the population, according to Aleksandr A. Oslon, president of the Public Opinion Foundation, who has delivered weekly briefings at the Kremlin for 15 years.

Mr. Olson’s company is one of several that conducts polls for government agencies, including a regular survey of 60,000 Russians, and a weekly poll of 3,000 that includes questions shared only with Mr. Medvedev’s and Mr. Putin’s teams.

Other pollsters seek to identify policy statements and political gestures that resonate with different segments of the public.

They helped put together Mr. Medvedev’s most recent yearly address, which dropped his trademark issue of modernization in favor of child welfare. And they help shape public appearances like Mr. Medvedev’s meticulous televised reminiscence of his role during Russia’s war with Georgia, which gave his approval ratings a significant boost.

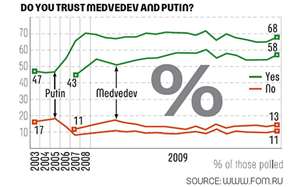

Both leaders, Mr. Putin and Mr. Medvedev are entering the campaign cycle with approval ratings that though enviable by most international standards, were lower this summer than at any point since 2008, according to the state owned All Russian Public Opinion Center.

More striking is a slide in the popularity of United Russia, the political party that Mr. Putin leads. To stop this drift, coming elections ‘need to attract the real support of the population,’ said Sergei A. Markov, a United Russia deputy. One option is to reach back to what became known as ‘the Putin’s phenomenon.’

Mr. Markov says Russia’s ‘passive majority’ will respond to a similar show of force this year, this time against drug dealers, criminality and moral decay. Though some, he noted, would prefer to take aim at ‘American hegemony.’

The opposite argument is coming from a liberal set of social scientists, who say the data shows the public wants more open and competitive political model.