Scientists say they have managed to turn patients’ own skin cells into healthy heart muscle in the laboratory.

They succeeded for the first time in taking skin cells from patients with heart failure and transforming them into healthy, beating heart tissue that could one day be used to treat the condition.

A research team in Israel led by Lead researcher Professor Lior Gepstein, said: “What is new and exciting about our research is that we have shown that it’s possible to take skin cells from an elderly patient with advanced heart failure and end up with his own beating cells in a laboratory dish that are healthy and young, the equivalent to the stage of his heart cells when just born.”

Heart failure is a debilitating condition in which the heart is unable to pump enough blood around the body. It has become more prevalent in recent decades as advances medical science mean many more people survive heart attacks.

At the moment, people with severe heart failure have to rely on mechanical devices or hope for a transplant.

Gepstein’s team took skin cells from two men with heart failure, aged 51 and 61, and transformed them by adding three genes and then a small molecule called valproic acid to the cell nucleus.

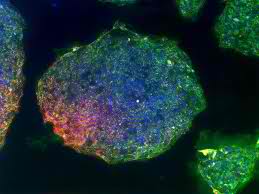

They found that the resulting human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) were able to differentiate to become heart muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes, just as effectively as hiPSCs that had been developed from healthy, young volunteers who acted as controls for the study.

Scientists turn skin cells into beating heart muscle.

The team was then able to make the cardiomyocytes develop into heart muscle tissue, which they grew in a laboratory dish together with existing cardiac tissue.

Within 24 to 48 hours the two types of tissue were beating together, they said.

In a final step of the study, the new tissue was transplanted into healthy rat hearts and the researchers found it began to establish connections with cells in the host tissue.

“We hope that hiPSCs derived cardiomyocytes will not be rejected following transplantation into the same patients from which they were derived,” Gepstein said.

“Whether this will be the case or not is the focus of active investigation.”

Experts in stem cell and cardiac medicine who were not involved in Gepstein’s work praised it but also said there was a lot to do before it had a chance of becoming an effective treatment.

The researchers say more work is needed before they can begin trials in humans.

Dr. Mike Knapton of the British Heart Foundation, said: “This is a very promising area of study.”