Malaria is spread by the Plasmodium parasite which invades human red blood cells.

So far attempts to develop a vaccine that prevents the organism entering cells have proved unsuccessful.

As little as a decade ago vaccine experts considered the challenge of tackling the mosquito-borne infection impossible.

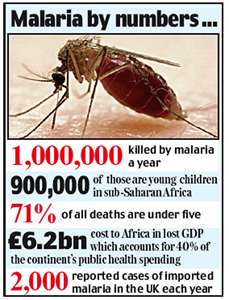

It is hoped the discovery will lead to new treatments or vaccines to combat the malaria scourge which claims a million lives a year.

A major obstacle has been that the parasite is so adaptable. When entry through a molecular ‘receptor’ on the cell wall is blocked, the organism switches to another.

The new research has identified a single red blood cell receptor that appears to be essential for malaria infection.

The scientists showed that the parasite has to interact with the receptor in a certain way to gain entry.

They also demonstrated that disrupting this interaction completely prevented the parasite invading red blood cells. Crucially, this was true across all parasite strains tested, suggesting that the receptor was a universal entry pathway.

”By identifying a single receptor that appears to be essential for parasites to invade human red blood cells, we have also identified an obvious and very exciting focus for vaccine development,” said co-author Dr Julian Rayner, also from the Sanger Institute.

”The hope is that this work will lead towards an effective vaccine based around the parasite protein.”

Vaccinating against malaria will be the most cost-effective and simplest way to protect populations against the disease.

”The discovery of a single receptor that can be targeted to stop the parasite infecting red blood cells offers the hope of a far more effective solution.”

Professor Adrian Hill, Wellcome Trust senior investigator at the Jenner Institute, Oxford, said: ”Recent reports of some positive results from ongoing malaria vaccine trials in Africa are encouraging.